The Ultimate - Indian Head Double Eagle

By Dr. Mike Fuljenz

That’s the goal we mortals strive to attain in myriad fields of endeavor. To climb the highest mountain … run the fastest race … pitch a perfect game … draw a royal flush – these are the kinds of accomplishments few of us ever achieve but most of us aspire to, every now and then, if only in dreams and fantasies.

In the world of collectible coins, there are dozens of superstars – gold pieces, silver dollars and even nickels and cents – that command small fortunes (and sometimes very large ones) because of their great rarity, exceptional condition, unusual historical importance and often combinations of these attributes. But many numismatists agree that one stands alone as the brightest star of all – the single most desirable prize in the realm of coins. In short, the ultimate.

That stunning supernova is the 1907 Indian Head double eagle, the rarest, most majestic example of the dazzling gold coinage designed by famed sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. This coin – a unique proof pattern struck in extremely high relief – is the only example that shows the artist’s work exactly the way he meant it to appear. Intriguingly, it’s a composite of the two coins Uncle Sam issued bearing the artist’s designs: the beautiful Indian Head eagle, or $10 gold piece, and the elegant Striding Liberty double eagle, or $20 gold piece.

Patterns have been described as “might-have-been” coins. Generally speaking, a pattern is a coin struck by a government mint to demonstrate something new – a new design or inscription or perhaps a new denomination – and typically, though not always, struck in the same metal intended for use on regular coins of that type. Patterns carry a statement of value, but are not legal tender because they were never monetized.

|

| President Theodore Roosevelt ushered in what is now regarded as the renaissance of American coinage art. |

For many years, the Indian Head double eagle was known in numismatic circles as “J-1776” because that was the shorthand designation assigned to it by Dr. J. Hewitt Judd in his standard reference book United States Pattern Coins, Experimental and Trial Pieces. The name became part of the coin’s iconic status because of the coincidental association of its number, 1776, with the year of the nation’s birth. But after acquiring rights to the book about a decade ago, Whitman Publishing changed the designation to J-1905 in order to make room for new discoveries, since listings are shown in chronological order. The change dismays some purists, who see it as disrespectful of the coin’s special status as one of the crowning jewels of U.S. coinage. But eminent numismatist Q. David Bowers, editor of the book, says he heard no such objections when the numbering was changed in 2003. According to Bowers, 20th-century patterns had to be renumbered to permit insertion of the many 19th-century pattern varieties identified since the last previous printing.

The Indian Head double eagle is the same size and weight as the $20 gold piece first issued by the U.S. Mint in 1907, and its reverse design is virtually the same as that of the coin made for commerce – a breathtaking eagle in flight inspired by the reverse of the Flying Eagle cent. But instead of the striding full-length likeness of Miss Liberty that graces the issued double eagle, the obverse of the pattern shows a close-up of Liberty’s left-facing head wearing an Indian war bonnet – essentially the same portrait used on the regular $10 gold piece when it was introduced in 1907. On the pattern, as on the issued double eagle, the Latin motto E PLURIBUS UNUM is inscribed on the edge, with stars between the letters.

There are smaller distinctions, too – and if anything, these enhance the pattern’s appeal. Most strikingly, Saint-Gaudens placed the large inscription LIBERTY below the Indian Head, at the base of the obverse, and put the Roman numerals date on the reverse, engraved on the sun at the base of that side. On the issued double eagle, LIBERTY appears along the upper obverse rim, above the Striding Liberty. The date is located to Miss Liberty’s lower right. It’s shown in Roman numerals on the first coins made for commerce, which were struck in high relief; later in the year, the relief was permanently reduced and the date was converted to Arabic numbers. In yet another departure, the artist arranged 13 stars symbolizing the 13 original colonies along the upper obverse rim. On the final $20, there are 46 small stars around virtually the entire obverse rim, reflecting the number of states in the Union at the time. The version with 13 stars did end up being used in the same obverse location – not on the $20, but on the $10.

|

| William Sturgis Bigelow was a collector of Japanese and American art and a close friend of President Roosevelt's. He introduced the president to the artist Saint-Gaudens. |

Ed Reiter, former Numismatics columnist for The New York Times, finds these departures aesthetically highly pleasing.

“Few would argue that Saint-Gaudens’ two gold pieces rank among our nation’s most beautiful coins,” Reiter said. “But this radiant pattern blends the best elements of both of his regular-issue coins so masterfully that it outshines even these great works of numismatic art.”

If it were offered for sale today, the Indian Head double eagle could command $20 million or more, market insiders say. As it is, there are reliable reports that a serious buyer already has offered $15 million – and been rejected by the current owner, a dedicated collector who specializes in coins and medallic works by Saint-Gaudens. That’s nearly twice the auction record for a single U.S. coin: the $7.59 million paid in July 2002 for a 1933 Saint-Gaudens double eagle once owned by Egypt’s King Farouk. That record has stood for more than a decade, but it would almost certainly fade to a distant second if the ultimate U.S. coin became available.

This ultimate coin could be transformed overnight into something even more special: The face of American numismatics. For generations to come, its design could be the image Americans associate with rarity and value in U.S. coinage. Unquestionably, its price would be so sensational that news of its sale would be featured on front pages of newspapers big and small across the country … given prominent play on network newscasts … and trumpeted by large black headlines on all the major Internet Web sites. In the process, millions of Americans who never collected coins would gain healthy new respect for the hobby as a whole and particular admiration for the coin – this coin – that made them sit up and take notice that acquiring such collectibles is far more than just a penny-ante pursuit.

|

| Augustus Saint-Gaudens, at the personal invitation of the president, designed a much-admires inaugural medal for Roosevelt's second term. |

***

Why is this potential “face of numismatics” so little known today, not only among Americans at large but even among collectors? The answer can be found in an old, familiar adage: “Out of sight, out of mind.” The coin has been on the sidelines so long, closely held in a private collection whose owner has chosen not to sell or even display it, that it hasn’t received nearly as much publicity as lesser rare coins that have come up for sale in the last quarter-century, in some cases multiple times.

The last time it changed hands at public auction, the coin brought $475,000 at the official convention auction of the American Numismatic Association in 1981 – then an auction record for any coin struck by the U.S. Mint. Three years later, its last known owner – a group of partners headed by Jack Hancock and Bob Harwell of Atlanta – consigned it to Auction ’84, but bought it back for $467,500 when bidding failed to meet their reserve. Shortly thereafter, the partnership sold it by private treaty to a buyer identified only as “a major Northeastern collector” for what was described as a “mid-six-figure price.” The buyer reportedly is a former executive in the high-tech industry who has spent decades assembling an unparalleled collection of coins and other artwork by Saint-Gaudens, including numerous examples of the Ultra High Relief 1907 double eagle.

Since then, the market value of other major rarities has risen sharply from mid-1980s levels, breaking the million-dollar barrier in 1996 and topping that figure repeatedly during the intervening years. In the meantime, the ultimate rarity – the Indian Head double eagle – has remained, so to speak, in a pit stop as other coins have left it far behind in the race for recognition as the world’s most valuable coin. But if and when it comes on the market, it will almost certainly zoom to the head of the pack.

What qualifies this coin to be the face of numismatics?

For one thing, its own face is a thing of singular beauty. Its “Indian Head” portrait – so compelling on the $10 coin – is even more riveting in enlarged form on the $20. And the eagle on the reverse remains as magnificent as ever, underscoring again why Saint-Gaudens’ double eagle has long been regarded as the loveliest work of coinage art the U.S. Mint ever issued. The coin’s flawless appearance is equally phenomenal; the Judd pattern book describes it as a “Gem Proof.” Furthermore, the pattern is unique – the only coin of its kind struck in the adopted coinage metal – and thus has the rarest sort of rarity. (The American Numismatic Society owns an impression in lead, which is technically not a pattern but a trial strike. That piece is listed as J-1906 in the Judd book’s current edition, and previously was listed as J-1777, to denote that it’s viewed differently from the gold pattern.)

Beyond these extraordinary attributes, the Indian Head double eagle also can lay claim to being the most glorious achievement of the greatest collaboration in U.S. coinage history: the pairing of Saint-Gaudens, the pre-eminent sculptor-medalist of his day, with President Theodore Roosevelt, the dynamic chief executive who ushered in what is now regarded as the renaissance of American coinage art.

Roosevelt’s restless nature drove him to immerse himself in just about every facet of America’s national life – including the coins people spent. He considered U.S. coinage at the turn of the 20th century to be sterile, dull and totally unworthy of a nation then emerging as a player of growing significance on the stage of world affairs. He admired Saint-Gaudens’ work and deemed the peerless artist especially well suited to carry out his vision of new U.S. coinage inspired by the high-relief portraiture on the glorious coins of ancient Greece. This view was reinforced when Saint-Gaudens, at the president’s personal invitation, designed a much-admired inaugural medal for Roosevelt’s second term.

***

Even before the inaugural medal was done, Roosevelt evidently had resolved to seek Saint-Gaudens’ involvement in totally redesigning U.S. coinage. In a note to Treasury Secretary Leslie Mortier Shaw dated Dec. 27, 1904, the president wrote as follows:

|

| Roosevelt's was set on Saint-Gaudens' involvement in totally redesigning U.S. coinage even before the inaugural medal was done. |

“I think our coinage is artistically of hideous atrociousness. Would it be possible, without asking permission of Congress, to employ a man like Saint-Gaudens to give us a coinage that would have some beauty?”

Characteristically, “TR” found ways not only to circumvent Congress but also to overcome Saint-Gaudens’ misgivings about working with the Mint’s engraving staff – particularly Chief Sculptor-Engraver Charles Barber, with whom he had clashed bitterly in the early 1890s regarding the design of a medal for the World’s Columbian Exposition. This time, Roosevelt assured him, he would have a protector in the White House as they plotted what the president called his “pet crime.”

Although both men envisioned a complete makeover of all U.S. coinage, only five coins – the four gold pieces and the cent – were eligible for replacement at the outset. An 1890 law required congressional approval to change any coin’s design before it had been issued for at least 25 years – and under this law, Roosevelt told the artist, the nickel couldn’t be changed until 1908 and the half dollar, quarter and dime until 1917 (although, as things turned out, new silver coins actually debuted in 1916). Mintage of silver dollars was suspended at the time. “I suppose the gold coins are really the most important,” the president wrote. “Could you make designs for these?”

As he had feared, Saint-Gaudens encountered resistance almost from the outset from Chief Engraver Barber. The high relief desired by President Roosevelt required deep cutting of the dies, and Barber insisted that this was beyond the Mint’s capability. What’s more, he said, coins with such relief would need multiple blows, and this would be expensive and impractical.

Roosevelt was prepared for such objections. Anticipating Barber’s obstruction, he contacted Tiffany and Gorham, two nationally known New York City jewelers and silversmiths, to see whether their houses “could without difficulty at a single stroke make a cut as deep as this.” Both assured him they could do so. He then fired off a letter on Sept. 11, 2006 to Treasury Secretary Shaw stating, in part: “Mr. Barber must at once get into communication with Tiffany and Gorham, unless he is prepared to make such a deep impression without such consultation. Will you find out from him how long it will take, when the full casts of the coins are furnished you by Saint-Gaudens, to get out the first of the new coins – that is, the twenty-dollar gold piece, which is the one I have most at heart?”

Saint-Gaudens had been battling cancer for years, and his health was deteriorating steadily as he started work on the coin designs. Nonetheless, he plunged into the project with all the strength he could muster. Initially it was expected that the double eagle and eagle would carry identical designs. By early 1907, the artist had prepared models that featured the Striding Liberty and Flying Eagle designs that ended up appearing on the $20 coin. But in contemplating possible designs for a new cent, he had come up with the Indian Head design showing Liberty adorned with a feathered headdress – and though the headdress had been Roosevelt’s idea, the artist had come to believe that this, not the Striding Liberty, would make a better obverse for both gold coins.

He conveyed this to the president in a letter dated March 12, 1907, in which he wrote: “I like so much the head with the headdress (and by the way, I am very glad you suggested doing the head in that manner) that I should very much like to see it tried not only on the one cent piece but also on the twenty-dollar gold piece, instead of the figure of Liberty. I would like to have the mint make a die of the head for the gold coin also, and then a choice can be made between the two when completed. The only change necessary in the event of this being carried out will be the changing of the date from the Liberty side to the Eagle side of the coin.”

Roosevelt instructed the Mint to strike a $20 gold piece using this combination, and it did so in March 1907. Just one such specimen is thought to have been struck – the coin now revered as the Indian Head double eagle pattern. After Roosevelt decided to proceed instead with the Striding Liberty obverse, the Mint – at the president’s direction – struck about 20 gold double eagles in similar extremely high or “ultra high” relief bearing the adopted design. These were used as presentation pieces and are highly coveted today, often commanding seven-figure prices.

After seeing the Indian Head pattern, Saint-Gaudens pressed for weeks for adoption of this design on the regular $20 coinage, but then he had a change of heart and said the Striding Liberty was better after all. By then, Roosevelt was wearying of the delays caused by Saint-Gaudens’ illness, and the artist’s uncertainty triggered a snap decision. On May 25, in an effort to satisfy himself and also mollify Saint-Gaudens, the president notified Mint Director George Roberts “… that the designs for the Double Eagle shall be the full figure of Liberty and the flying eagle, and the design for the Eagle shall be the feather head of liberty with the standing eagle.”

|

| Roosevelt's restless nature and dynamic personality drove him to immerse himself in most areas of America's national life. |

“It is now settled,” the exasperated president declared.

The “standing eagle” cited in Roosevelt’s directive was one of two alternative designs created by Saint-Gaudens for possible use on the double eagle. Its depiction of an eagle in repose has won high acclaim for artistic merit – lending irony to the fact that it was a bit of an afterthought at the time the president chose it. In July 1907, Mint Director Roberts suggested replicating the $10 coin’s design on the two smallest gold coins, the half eagle and quarter eagle ($5 and $2½ gold pieces). It was assumed that these would also be fashioned by Saint-Gaudens – but the great artist died on Aug. 3, not quite living long enough to see his exquisite eagle and double eagle released into circulation.

The spirit of Saint-Gaudens did infuse the smaller coins, which debuted in 1908 – for Bela Lyon Pratt, the artist Roosevelt chose to design them, adapted the “standing eagle” for the coins’ common reverse. Pratt had been one of Saint-Gaudens’ students and in “borrowing” the master’s artwork, he seems to have been paying homage to his mentor, as well as carrying out the Mint director’s wishes. The portraits are virtually the same, with the notable difference that the eagle is incused – or sunken below the surface – on the two Pratt coins.

***

The ultimate rarity owes its very survival to an ultimate irony. Amid the confusion and uncertainty following its production, the double eagle pattern wound up not in Saint-Gaudens’ hands or the U.S. Mint’s coin cabinet, but rather in the effects of Charles Barber, the Mint chief engraver who fought tooth and nail to thwart Saint-Gaudens’ coinage redesign. Following Barber’s death in 1917, his estate sold the coin to Waldo C. Newcomer, a prominent Baltimore collector. There is no record of how Barber came to own the coin, but the situation has given Saint-Gaudens’ admirers fodder for delicious speculation.

Bob Harwell, one of the partners who owned the coin in the early 1980s, says the seeming contradiction “has always been interesting to me.”

“Barber was not very happy when Saint-Gaudens got the go-ahead to redesign our coinage,” Harwell comments, “but he certainly thought enough of this coin to have it in his estate when he died. I’ve always wondered how he got it – whether he put $20 in the till and kept the coin.”

Although the current owner of the coin has never been publicly identified, its pedigree includes some of the most famous names in numismatics. In 1933, Newcomer offered to sell it for $10,000 to John Work Garrett, whose family formed the fabulous Garrett Collection – but Garrett declined the offer and the coin was then sold to Frederick C.C. Boyd, a well-known New York City collector now enshrined in the ANA Hall of Fame. In the mid-1940s, Boyd’s wife sold the coin to Abe Kosoff and Abner Kreisberg, leading New York dealers at that time, for $1,500. They, in turn, sold it to Egypt’s King Farouk for slightly less than $10,000. Kosoff reacquired the coin in 1954, when the Egyptian government sold Farouk’s world-class collection of rare coins. The price was 1,200 Egyptian pounds, or roughly $3,400 in U.S. funds.

Kosoff placed the coin this time with an American numismatist, Roy E. “Ted” Naftzger Jr., who subsequently sold it to Dr. J.E. Wilkison, a Tennessee collector who specialized in patterns, for $10,000. In 1973, this and other rare patterns were acquired from Wilkison by Paramount International of Englewood, Ohio. Paramount traded the coin to A-Mark Financial – which then sold it to professional numismatist Julian Leidman in 1979 for $500,000. It was Leidman who consigned it to the 1981 auction where the Hancock and Harwell partnership acquired it.

***

Jimmy Hayes, a former five-term congressman from Louisiana, is a true connoisseur of rare coins, having assembled a gem mint-state type set of first-year coins from every U.S. series, including gold. Hayes never owned the Indian Head double eagle, but he had a chance to buy it while it was in Wilkison’s possession. He was still in law school and didn’t have the resources then – but he was keenly aware of the coin’s lofty place in the pantheon of U.S. numismatics.

|

| Sturgis also put Roosevelt in contact with Bela Lyon Pratt, on of Saint-Gaudens' students. Pratt designed the smaller gold coins that debutted in 1908. |

“If I were to draw up a list of the most desirable U.S. coins, this would be first,” he declares. “It’s the perfect definition of the qualities that come into play.

“First of all, it’s unique – a unique gold coin. Both sides ended up on regular circulating coinage. A U.S. president was directly involved in its creation – and not just any president, but one of the most popular. It was designed by the most gifted sculptor of his era – and arguably any era – in the United States.

“All these things combine to make it just an extraordinary rarity. And without any doubt, if you put everything that everyone wants to buy into the same auction, this piece would not only beat them, but I don’t think second place would be anywhere close.”

How much might the coin bring if it came up for sale today? Rather than hazard a guess, Hayes points out that the $15-million offer has already been turned down.

“That’s a pretty good indication right there,” he remarks. “Someone has offered nearly twice the highest price you can compare anything to – not a theoretical price, but a firm offer. And the offer was rejected.”

To his way of thinking, the 1933 double eagle – the current record-holder – “isn’t even in the same league” with the Indian Head double eagle.

“First of all,” he says, “the ’33 double eagle was a coin intended for circulation, even though it didn’t circulate. Second, the coin was never unique; the Mint made nearly half a million before melting almost all of them. It’s unique now in the sense that only one is available, but that’s because of some legal barriers. The fact of the matter is, we know there’s over a dozen of them out there. And it does not have any history, other than the fact that its date coincided with an executive order to stop the minting. Otherwise, it would be an expensive coin but no one would think that much of it. It would be the same as a 1933 $10.”

Does the fact that it’s a pattern, not a regular-issue coin, diminish the appeal of Judd-1776 (or, if you prefer, J-1905)?

“I think it increases the coin’s desirability,” Hayes says, “because it’s one of the few patterns to carry a design that ended up on a different denomination than the one in which it was struck. There are very few patterns that fall into that category – in addition to which, it’s a piece that’s associated with a president, not simply a Mint engraver’s concept of something that might be done.”

***

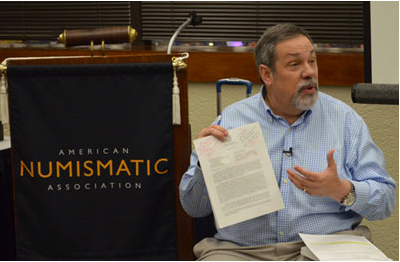

John Dannreuther, co-founder of the Professional Coin Grading Service (PCGS), was one of those who teamed up with Hancock and Harwell to purchase the pattern in 1981. He thinks the coin would generate extensive media coverage even if it brought just $10 million – and tremendous publicity if it sold for significantly more.

“A $20-million coin would certainly cause a lot of excitement,” he says. “Look, it made the local paper here in Tennessee when the 1870-CC no-arrows dime brought $1.84 million recently at the ANA auction in Philadelphia. That made the paper here because it was picked up by the national news. We see this every time a coin sells for a couple of million dollars.”

Even at $20 million, though, Dannreuther is convinced that the coin would be underpriced.

“Recently,” he says, “I Googled the top 100 artworks of all time, and there are many that have brought over 100 million dollars. There are pictures and sketches that have brought tens of millions of dollars. So by comparison, historic rare coins are cheap.

“This coin is a national treasure. It should obviously be worth as much as a painting by Jasper Johns or Robert Rauschenberg.” (People in Beaumont, Texas, where the author’s coin business is located, feel a special affinity for Rauschenberg, since he’s a native of nearby Port Arthur.)

“Look,” Dannreuther asks, “how can an Andy Warhol painting be worth 80 million and this coin only be worth 15 or 20 million? This is certainly a more iconic image of America than Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe. But the people who collect art are used to paying 10 million or 20 million or 30 million dollars for an artist that most of us have never even heard of.

“People figure, hey, it’s a coin, so it can’t be worth as much as a piece of art. And yet, a coin such as this is a piece of art. I’ve been to the Saint-Gaudens Museum in Cornish, New Hampshire, and that’s one of the most beautiful places on this earth. To walk through there and see all those plaster models and the miniature Shaw Memorial and all the stuff that’s there in his former home is amazing, and you realize what a great artist he was.

“Saint-Gaudens was a tremendous artist – certainly better than Andy Warhol.”

***

Bob Harwell considers the Indian Head double eagle to be “without question the single most important U.S. gold coin.” The only other one that comes close, he says, is the 1849 Liberty Head double eagle, the nation’s very first $20 gold piece, which also is unique. Opinions are divided as to whether the 1849 coin is a regular issue or a pattern – but Harwell doesn’t think it really matters.

“What matters,” he says, “is that one of these coins – the Indian Head pattern – can be owned by an individual collector and the other, the 1849, cannot because it’s in the Smithsonian Institution. You can put a price on the Indian Head $20 because it’s in private hands and the owner could sell it if he chose.

|

| Roosevelt's "pet crime" generated some of the most beautiful coins in U.S. history and left us with a few examples of the coin that could be the new "face of nimismatics". |

“There are guys who say the 1849 is worth the same as the Indian Head pattern, but you can’t put a price on a coin that’s in a museum. It’s never going to be sold, so what’s the point?”

Its association with Saint-Gaudens gives the Indian Head pattern another big edge, Harwell adds.

“For our generation,” he says, “the Saint-Gaudens coins are clearly the most important. And this is the only coin to carry Saint-Gaudens’ original design for the double eagle – the one that he wanted to be used.”

There was good reason, he says, why David W. Akers showed an embossed image of the coin on the cover of his landmark book on U.S. gold patterns.

Harwell’s best guess is that the Indian Head $20 would bring $25 million if it came on the market. But he, like Dannreuther, views it first and foremost as a great work of art.

“What’s it worth? Well, ‘The Scream’ by Edvard Munch just sold for mega-money [$119.9 million], and I consider this a far more appealing piece of art. To me, it’s the ‘Mona Lisa’ of the coin business.”

Harwell has owned some exceptional coins through the years. But none has given him greater satisfaction than the Indian Head double eagle.

“I look back on those four years when we owned the coin as a wonderful time,” he says. “It’s the greatest coin I know of, and owning it was a once-in-a-lifetime thrill.

“It was like owning a very special piece of numismatic history.”

The famous actor and coin collector James Earl Jones once said, “Money is history in your hands.” And who are we to argue with Darth Vader.